What do dry eye tests mean? (Part 2)

One of the reasons to seek out a dry eye specialist, is that to be a dry eye specialist, they should have invested time and money into obtaining and understanding up-to-date, specialty-specific technologies for diagnosing and treating dry eye disease. Thanks to the many engineers, companies and doctors leading the way – there are now MANY such technologies available and virtually no specialist will have (nor are likely to need) all of them.

If you wonder why many specialists charge what seem to be exorbitant prices for their services, it is worth noting that many of the diagnostic technologies cost upwards of $30,000 each and treatment devices can run $100,000 each - and the average clinic will have several such technologies. There are also the usual overhead costs of running such facilities and since inflation has gone up dramatically, hiring and keeping good staff who can run and service these machines, is at an all-time high. There is also a much-needed serious commitment on the part of the doctors (and their staff) to keep up with all of this technology, so in the end, it is never truer said, than: “you are likely to get what you pay for” in this field.

Now with that behind us, let’s get into the more specific dry eye exam.

In my center, perhaps the most useful device we use to examine and educate our patients with, is the so-called keratographer. This multi-functional machine allows us to image the Meibomian (oil) Glands in the eyelids, to monitor their function by determining the “Non-Invasive Tear Break-Up Time” (NITBUT), the “Inter-Blink Interval” (IBI), and to image the surface of the eye with diagnostic dyes (looking for dry spots, and the smoothness – or lack of smoothness – of that surface). It also can read the curvature of the cornea (useful in determining the power of focus of that part of the eye), to measure the volume of tear supported on the lower eyelid and to video the characteristics of the lids during the blink reflex. Some have software to create automated reports that can be used to relay information to the referring doctor or other specialists and may serve as a useful tool for the patient to keep track of their findings.

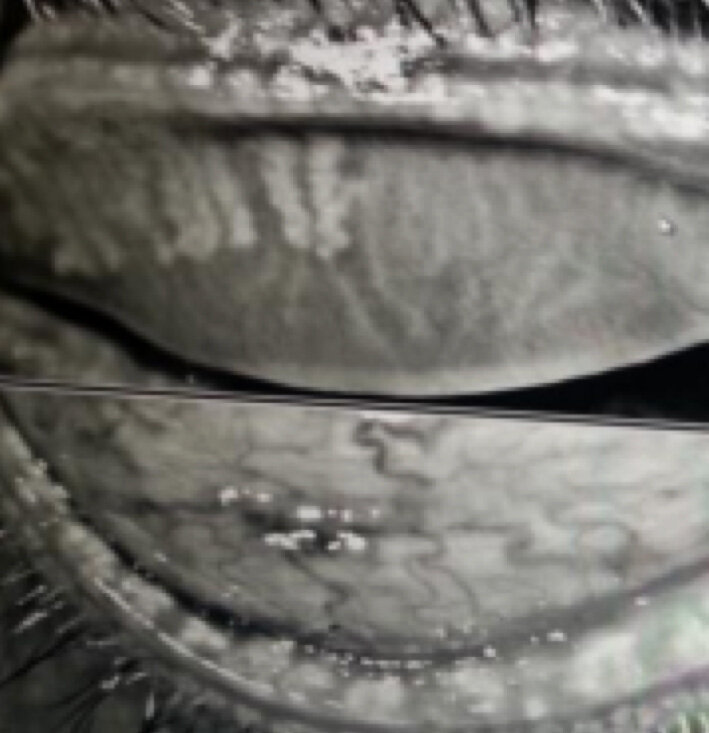

Imaging the oil glands is critical, as 85% of dry eye patients have a measure of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD) as a cause. The majority of these have visible abnormalities of these glands when photographed with InfraRed (IR) cameras such as those in the average keratographer. It is common to estimate the percentage of remaining gland tissue from these photos, though I find that IR photography tends to underestimate the amount of remaining tissue, as it appears to highlight only the active, oil-bearing portions (where a technique called transillumination can sometimes reveal what appears to be substantially more tissue). As these glands clog up, they tend to “constipate,” which causes them to dilate (presumably from increasing pressure trying to force their oils around the obstruction), and then to whither (atrophy). The eventual end-result is a loss of the glands and it can be difficult (if not impossible) to fully rejuvenate them with present technologies.

Meibomian Glands appear white, should run the full length of the rolled-over eyelid, and number 25-30 per lid. Most of these MGs are short, withered remnants - indicating an advanced degree of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD).

This photographic evidence is often alarming – both to the specialists and to their patients – and raises a significant “call to action.” It is hard to refute this level of evidence, even when symptoms and other clinical findings do not seem to appear quite as bad as this would otherwise suggest. What we’ve learned is that even as few as 6-functional glands per lid can provide sufficient oil so as provide a decent tear function. Because we are born with 25-30 glands per lid, this means we can lose up to 20-25 of them before we become aware we have a problem. Now that we are living longer lives, and using our eyes far more than previous generations would (given electricity to light our environments has only been common in households since the early 1900’s and power digital devices we use in all walks of life these days are common only in the last 30 years), it is incumbent on eye doctors to do everything in their power to ensure their patients have tear glands capable of lasting their patient’s lifetimes (and matching their lifestyle demands). I would have a hard time trusting a dry eye “specialist” to provide optimal care without the ability to image these glands. Next week, I’ll discuss some of the other functions of the keratographer and how we interpret these results!